Django Runtime #

In our first Django lab, we learned about the request/response lifecycle, how Django’s many different parts work together to serve responses to clients. In this second lab on Django, we will consider a longer lifecycle, how Django works as a Python program from startup to shutdown. You will also learn about different ways of running Django, and we’ll go into a bit more detail about requests and responses.

💻 Let's begin by starting the Colorama app in a Terminal window. This lab picks up where Part I left off.

cd ~/desktop/making-with-code/unit05_webapps/lab_colorama_yourgithubusername

poetry shell

python manage.py runserver

A. Django management commands #

Every time you run Django, you run manage.py with some command. In Part I, you ran two management commands, migrate and runserver. You also saw many more, when you ran python manage.py --list. (You can learn more about any command by running python manage.py runserver --help.)

Let’s explore a few more commands.

[Database management] #

Your app stores its state in a database. In other words, all its records–usernames, content, never-ending records of every detail of user behavior, financial details (for apps like PayPal), your sexual orientation and who you find attractive (for dating apps), whether you have cancer (electronic medical records)… your whole online life.

If anyone ever got access to your app’s database, it could be a disaster for your users. Unfortunately, this happens all the time. (This is a great reason for using a framework like Django rather than trying to do it all yourself.)

Somewhat less disastrous is the situation where an app accidentally loses its own database, because of a careless programmer mistake (done that!), because a hard drive fails, or perhaps because you forgot to pay your web hosting bill (happened to a friend!) Users would find that their account no longer exist, nor does any of their content. After a restart, the app would behave as if it had just been launched for the first time. For apps in production (meaning they are available to real-world users), regular database backups are essential. That way, even if disaster strikes, at least you can restore the app to the way it was this morning, or last week, or whenever you last backed up the database.

Django has some nice built-in tools for database backups, which will provide us with a chance to practice using some new management commands.

💻 Back up your app's database.python manage.py dumpdata > backup.json

💻 Now that you have a backup of your database, let's test it, shall we? Delete your app's database.Note that the

>redirects the output of a command into a file.Try

dumpdatawithout> backup.json; you’ll see all the data printed to your Terminal window.

rm db.sqlite3

💻 Let's see what happened by starting to server.Careful! This is permanent. Your backup should work, but we’re only suggesting this because we assume you won’t be heart-broken if you lose the colors you previously created.

python manage.py runserver

💻 We can apply database migrations to re-initialize the database:The homepage still works because its view doesn’t access the database. But the color list page crashes.

python manage.py migrate

💻 Now let's restore data from your backup:Now you have a fresh clean database. The color list page should load, but there won’t be any colors.

python3 manage.py loaddata backup.json

Double-check the color list page; all your colors should be back.

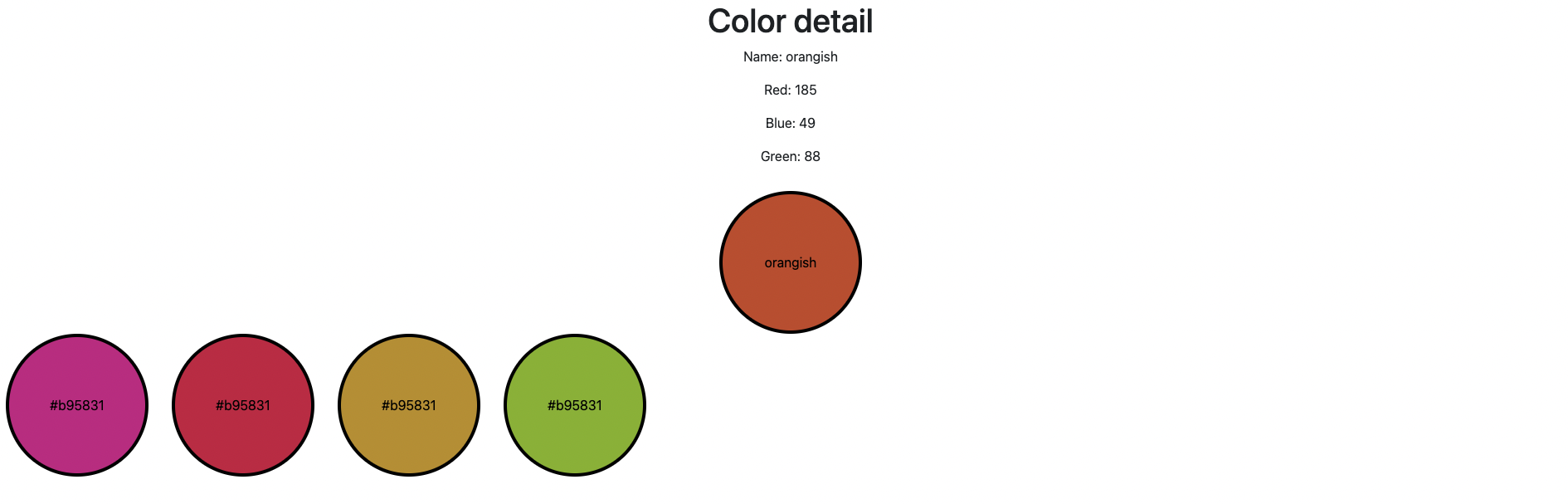

B. Adding color detail page #

Now let’s add a new feature to the app: a detailed page for each color This is going to require extending the app at every level we’ve studied so far. We’ll start at the “outside” with URL routing, and work our way “in” to the models.

- We need to add a URL route for showing a color. Wo avoid ambiguity, we’ll

refer to colors by the unique ID each is assigned by the database. These URLs

will have the form

colors/23,colors/155, etc. - We need a new view to handle these URLs.

- We’ll update the color list template so that each color swatch is a link to that color’s page.

💻 Add a view to handle the color detail route:

color_app/views.py:

| |

- What do you think the purpose of the

pkparameter is?

💻 Add a URL route. What file does this path go in?

| |

- How do you think you will access this new URL path?

💻 Create a new file for the color detail template:

color_app/templates/color_app/color_detail.html.

| |

- How can you display the other fields from the Model (red, green, blue)?

💻 Add a link from the color list template page to the color detail:

color_app/templates/color_app/color_list.html. Here is the link pattern. How should you use it?

| |

Congratulations! You just added a new feature to the app!

C. Palette Generator #

Now, let’s use the methods in the Color model to create a palette generator. Each color detail page will shows a color palette of colors that go nicely together.

You will need to:

- edit the

color_detailview - edit the

color_app/color_detail.html - understand how

adjust_hue()works

D. Deliverables #

⚡✨ Once you've successfully completed the lab:💻 Push your code to Github.

- git status

- git add -A

- git status

- git commit -m “describe your code and your process here”

be sure to customize this message, do not copy and paste this line

- git push